The father and friends of Max Larson along with others at Loyola call for educational and risk prevention resources concerning the fentanyl crisis.

‘My Beautiful Boy’: Student Died from Fentanyl Poisoning in Dorm

Content warning: Death, overdose, drug use

On the early morning of Oct. 29, Loyola sophomore Max Larson took what he believed to be Xanax — an anti-anxiety drug he obtained from a dealer who assured him “they’re legit.” That afternoon, he was found dead in his Bellarmine Hall dorm room, having died from fentanyl poisoning.

Fentanyl is a fatal synthetic opioid that is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more powerful than morphine, according to Luis Agostini, the public information officer for the Chicago Division of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Fentanyl is being laced into nearly every category of illicit drug and pressed into pills that look like they’re legitimate pharmaceutical pills, he said, like Oxycontin, Percocet, Vicodin, Adderall and Xanax.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of unnatural death for those aged 18 to 45, the majority of which are caused by synthetic opioids like fentanyl, according to Agostini.

Because social media platforms play a significant role in this “epidemic,” Agostini said education for students, faculty, staff and administrators is vital. At Loyola, those who are calling for reform said the university should be implementing risk prevention strategies like drug testing strips, overdose reversal kits and educational resources.

This includes Max’s father Larry Larson who reached out to The Loyola Phoenix after he felt he wasn’t getting traction with the Chicago Police Department.

“I can’t stand the thought that his death will mean nothing,” Larry Larson said. “If not, at least helping save another person. That’s the least and the most I can hope for.”

Max Larson was a 19-year-old undergraduate student in the Quinlan School of Business. In a bereavement notice, Campus Ministry wrote he “will be remembered for his quiet ambition, his academic successes, and the respectful way he treated everyone.”

Born in Brooklyn, he was Larry and Janis Larson’s only child. Describing his son as “my beautiful boy,” Larry Larson said he was so proud of his son in all facets of his life — academics, friendship and even the piano, where Max had “natural talent for improvisation.”

“The nicest thing I own is my piano, and that piano was to be Max’s,” said Larry Larson, a trained musician. “And now I can barely — I can’t look at it.”

His mother, Janis Larson, said no one “could possibly comprehend the severity of the loss of your child.”

“He was very lovable, he was very social,” Janis Larson said. “He had a lot of friends and there were a lot of people who were really broken that he’s gone.”

Among the friends was Meda Kerr, an international business and visual communication double major, who helped organize a vigil for Max on the shores of Lake Michigan Nov. 6.

Kerr, who said she has struggled with anxiety and depression, said Max Larson was her “number one emotional support person” at Loyola and would constantly reassure her she needed to be herself and not “get in [her] own way.”

“It’s so sad because once he died, I was like, ‘You know what? You’re so right,’” the sophomore said about Max’s advice. “It was like living for him, being the things he knew and loved.”

The night Max died, Kerr was babysitting her younger brother who lives in New York and had pizza with Larry and Janis Larson in Brooklyn. Kerr told Max she would pick up some clothes for him while there.

“He calls me during our dinner and he says, ‘Hey, don’t forget my black jacket,’” Kerr said. “We all heard his voice the last time together.”

The next afternoon, one of Max’s closest friends and a resident assistant on the first floor of Bellarmine, Macs Mercer, checked in on his friend who hadn’t been responding to texts.

When he opened Max’s unlocked door, Mercer found him lying dead on the floor. Mercer said he dropped his phone twice trying to find the right number to call and within 30 seconds, he and the second floor RA called Campus Safety.

“A lot of times when I think about him, it’s not the sadness,” Mercer said. “I can just focus on, ‘Oh, there’s good things that happened.’”

Campus Safety declined to comment on specific cases, but Commander Tim Cunningham said the fentanyl crisis is not “foreign” to their team.

“There’s no honor amongst drug dealers,” Cunningham said. “You think that you are being sold something by someone you trust, and there’s no guarantee that you’re buying what you actually think you’re buying. I think that’s an important message to get across.”

Max Larson’s cause of death was determined Nov. 26 to be an accidental overdose on fentanyl, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office.

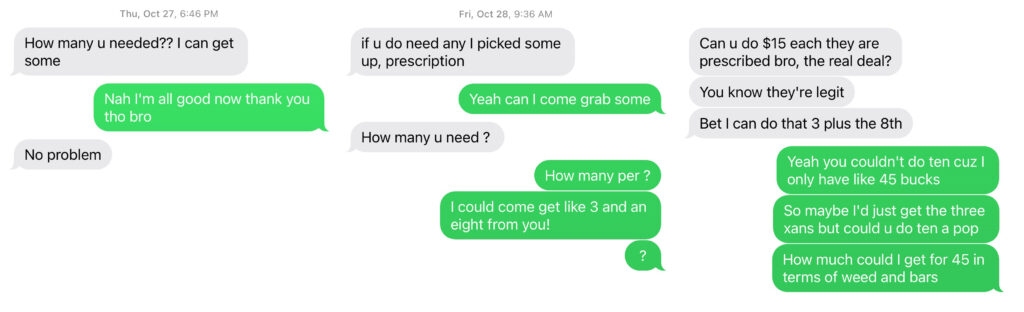

Around the same time it was confirmed his son was poisoned with fentanyl, Larry Larson said he found the apparent text conversations between his son and his dealer.

“if u do need any I picked some up, prescription,” the dealer sent on the morning of Oct. 28, according to screenshots obtained by The Phoenix. “Can you do $15 each they are prescribed bro, the real deal? You know they’re legit.”

Larry and Janis Larson said they had been asking for updates on the case and received no response from CPD for three to four weeks. During this time, he sent the police these screenshots and the phone number and said they still received no response.

Eventually, Janis Larson, a neurophysiology technician, said she was told “the wheels of justice turn slowly.”

When asked about this lack of response, CPD News Affairs wrote, “This is an ongoing investigation, the details of which cannot be shared.”

Agostini said the DEA is currently working on Max Larson’s case and in order to “maintain the integrity of the investigation,” he refrained from further comment.

“The material result of that, I think, was someone else could have died during that period,” Larry Larson said. “It would have been very easy for another Loyola student.”

Larry Larson said he knows the police are dealing with multiple narcotics cases but because of the way the police have handled it, it feels like it didn’t happen.

On the day Max Larson died, four other Chicago men died from an accidental overdose caused by fentanyl, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner Maps. In the past five months since that day, over 450 people have died an accidental opiate-related death in Cook County, according to the same data.

Sarah Richardson, a grants research specialist in the Office of Substance Abuse for the Chicago Department of Public Health, said there were 1,400 fatal opioid overdoses in the city during 2021 — more than homicides or traffic incidents. She added there are around 40 opioid overdose calls to 911 each day, approximately three of which are fatal.

James DeFrancesco worked at the DEA for nearly two decades and is currently the program director of the Forensic Science Program at Loyola. With the DEA, he said he participated in drug raids and processed labs in Mexico where the “precursors” for the laced drugs are shipped to from “eastern countries” like China. The reason dealers are turning to fentanyl is because it is a “good profit alternative to heroin.”

“They have full control over the entire process,” said DeFrancesco, explaining fentanyl can be produced in “any well-established lab” in just three to four steps.

In his lab in the basement of Flanner Hall, DeFrancesco has a collection of small bags, lottery tickets and tinfoil he has found on walks around campus. All of these items, he said, are ways drug dealers distribute heroin.

In addition, social media is also a driver in the increase of opioid overdoses, according to the DEA’s Agostini.

“What we’re finding, essentially, is that the accessibility to illicit drugs from both the dealer and the individual that is looking to get their hands on drugs is more accessible than ever before,” Agostini said.

All of this, DeFrancesco said, is a product of Loyola’s place in Chicago.

“For good or bad, Loyola’s within the city limits, and Loyola experiences all the good and the bad the surrounding area can provide,” DeFrancesco said.

Kerr recalled a time when Max Larson said he was pushed a free dime bag of cocaine as a sample on West Rosemont Avenue during their first year at Loyola.

A 19-year-old Loyola student diagnosed with ADHD, who requested their name not be published, said they have bought and sold Adderall — a prescription drug to treat ADHD — on campus before. This student did not know Max Larson.

The national Adderall shortage, announced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in October, has prevented the student from obtaining their prescribed drug and has been a “barrier” for the student to clean their room, do laundry and function.

“There’s a pharmaceutical systemic failure there as well, and that’s when you get this entry point for a lot of people into illicit buying and selling of these medications and substances,” the student said.

The student said the alcohol and cannabis modules first-year students are required to take “are nowhere near enough education and harm reduction for these issues.”

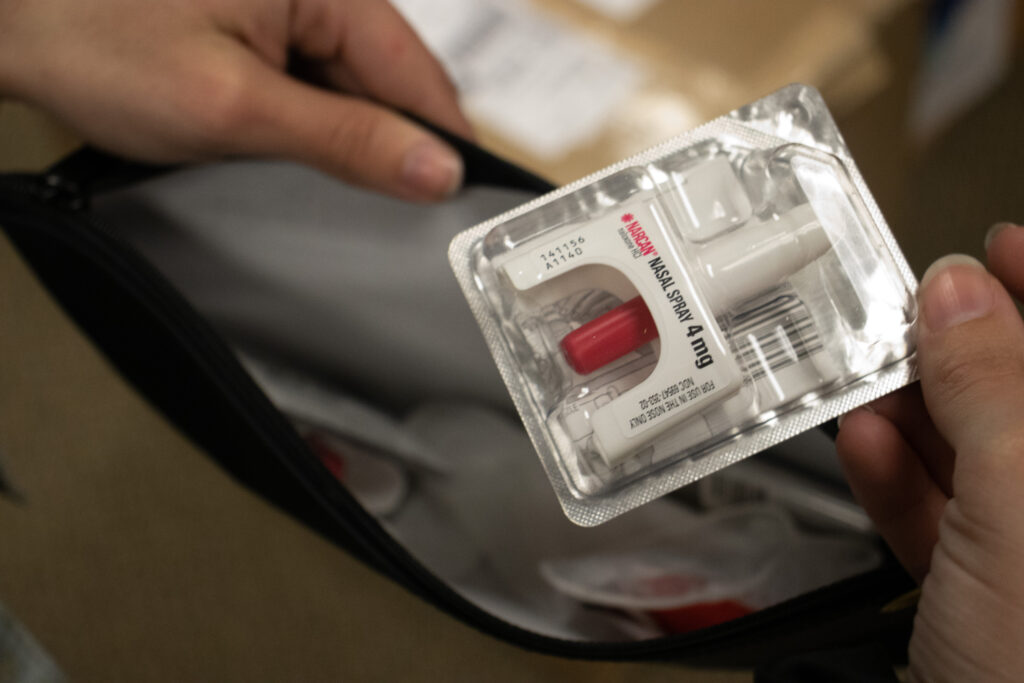

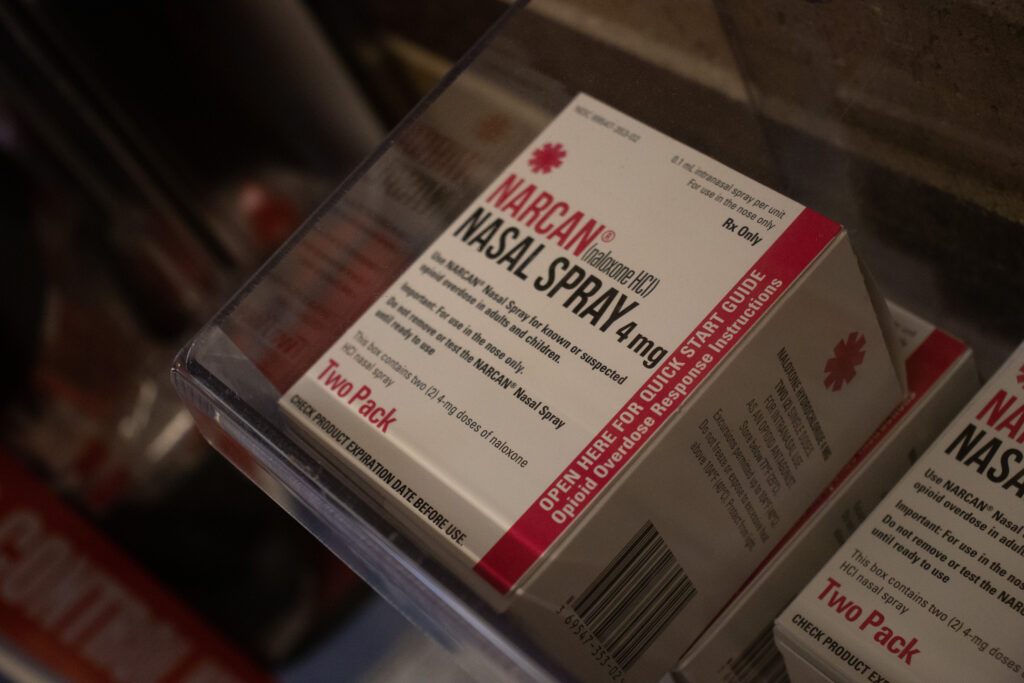

One thing they suggested be included was Narcan training for students. Narcan, a naloxone nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, was approved for over-the-counter, non-prescription use in March, according to the FDA.

Cunningham said all Campus Safety officers have been carrying Narcan since 2017 in case of an overdose at Loyola, and he is “not opposed” to Narcan being available on campus.

Ben Bryan was recently elected vice president of the Student Government of Loyola Chicago (SGLC), The Phoenix previously reported. In March, as the chair of the Safety and Wellness Committee, he proposed a bill that would “formally recommend” opioid awareness training and the distribution of Narcan around campus.

Bryan, a biology major with a pre-health emphasis, was “propelled” to write the resolution because he lived in Bellarmine last fall and heard about Max Larson’s death.

In addition, the resolution — which was passed by unanimous decision in the SGLC senate — suggested fentanyl testing strips be available at the front desk in the Damen Student Center and the Wellness Center.

“I just wanted a high-activity area, but then I also wanted the Wellness Center, because I feel like that’d be their first thought,” Bryan said.

In December, a month after Max Larson’s death, the Wellness Center sent an email to the university community detailing their alcohol and drug policies, that mentioned the “dramatic increase in the number of overdose deaths nationwide due to fentanyl” and said to “stay tuned for more information this spring from the Wellness Center.” In the four months since, there has been no update.

Joan Holden, the Wellness Center’s director, said this portion was written by Mary Duckett, who stepped down as the alcohol and other drug educator at Loyola in February. Duckett declined to comment.

Director of Health Promotion Mira Krivoshey said the Wellness Center originally planned to host Narcan training for students — and it is “still a priority.” The Wellness Center also has over a hundred fentanyl testing strips available that were provided by the Chicago Department of Public Health, but are still trying to understand how it would be implemented at the university. This was also coordinated by Duckett, whose former position is still open on the university’s career portal.

Kayla Turner, the substance misuse prevention specialist for DePaul University’s Office of Health Promotion and Wellness, said Loyola is “one of the only Chicago schools that has been able” to acquire fentanyl testing strips.

DePaul’s entire Office of Health Promotion and Wellness, the housing and residence life staff and all RAs at DePaul have received Narcan training, according to Turner. They also provide this training for any student organization that requests it.

“The Narcan training comes with a long PowerPoint presentation that explains a lot of the statistics, the data around the opioid crisis and things like that and being able to recognize an overdose,” Turner said.

In addition, Narcan kits — containing the nasal spray and instructions — are dispersed around their campus.

To administer Narcan, the one administering the nasal spray must insert the top of the nozzle into either nostril, tilt the person’s head back and press the red plunger firmly, removing after giving the dose, according to Emergent Biosolutions, who produces the drug. Signs of an overdose include slow or irregular breathing, small “pinpoint pupils” and the person not waking up to their name or touch.

The Chicago Division of the DEA covers most of Illinois and all of Wisconsin and Indiana, according to Agostini. His role includes engagement with educational institutions, including Northeastern Illinois University.

Dr. Jennie Lasko, the interim director of their Student Health Services, said NEIU has done tabling in residence halls about opioids and overdose training with police, faculty and students.

At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where Larry Larson attended graduate school, they implemented naloxone boxes in all university housing in October, according to their assistant director for high-risk drinking prevention Jenny Damask. She said this was in response to two students who died in 2021 from fentanyl poisoning in the UW-Milwaukee dorms.

“Why don’t we have handouts for students?” Larry Larson said. “Why don’t we have Narcan or something available at the RAs office on every floor? Why don’t we have fentanyl drug kits available for students that they can get without questions being asked — all of which would save lives?”

Holden of the Wellness Center said there are a number of things to “hammer out” before tackling these topics at the university. Facilities, residence life, the dean of students and Matt McDermott, the associate director of external communications at Loyola, directed The Phoenix to the Wellness Center when asked to comment.

“The health and safety and well-being of our students is very important to us,” Holden said.

Although he won’t be an RA again next year, Mercer said he thinks Residence Life should train them on how to use Narcan.

“A lot of our RA training is sitting there, and we absorb information, but I feel like part of it could be CPR and Narcan and maybe how to use a defibrillator,” Mercer said. “I don’t know how to do that stuff. If I find someone, I can’t help.”

Outside of the university, because libraries are “trusted community institutions,” all 81 Chicago Public Library locations offer free Narcan at all branch entrances, according to Richardson. Since the initiative began in 2021, she said the Chicago Department of Public Health has distributed 5,643 Narcan kits.

Edgewater branch adult librarian Katy Linehan recalled a time pre-pandemic when a man fell down the stairs and she thought he was having a seizure. When the paramedics arrived, they administered Narcan and he “snapped right out of it.”

Professor Mary Heinz of Loyola’s Marcella Niehoff School of Nursing Community Nursing Center helped organize two opioid awareness presentations at the library March 20 and April 6.

Heinz, a nurse for 30 years, said it was a teaching project for the students in her Community Population Health class. She said the seven students, including junior Victoria Kurisu, who helped present were “advocates for the people.”

“We can’t judge people who are going through it,” Kurisu said about addiction. “Instead, we have to educate and find ways to give resources in order to help them, and that starts on an individual level.”

Linehan, a Rogers Park resident, said learning how to use Narcan and identify an overdose is especially important to her because she is constantly working with the public.

Max’s mom Janis Larson said stories like her son’s are important, because they resonate with people in their hearts and can affect change for the better.

“We know that young people take risks,” Janis Larson said. “When I look back at my own childhood, I think, ‘Why am I here and Max isn’t?’”

Kerr said it is enraging, irresponsible and disrespectful the university has said nothing about how Max Larson died. Campus officials declined to comment on specific cases.

“I would like everyone to know this,” Kerr said. “I would like everyone to be aware of this. I’d like there to be no more Maxes.”

She added that “at the minimum,” she wants to make sure people aren’t bystanders and referenced the Good Samaritan Policy at Loyola, which allows students to report crisis situations involving drugs or alcohol without punishment.

Topics

Get the Loyola Phoenix newsletter straight to your inbox!