Writer Julia Soeder explores the positives and negatives of public photography.

One must ask themselves if humans were meant to have the power to document everything that happens to them in the palm of their hand.

The dawn of smartphones has led to a general fear of being photographed in public. At any moment, a push of a button could lead to an image of someone living forever on the device of a stranger. It feels as if such an action should be protected against — but the opposite is true.

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution allows a person lawfully in a public area to take a photo of anything plainly visible, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Social customs would flag a problem with this definition. While I’m within my rights to take a picture of a stranger across from me in a public space, this doesn’t stop the stranger from rightfully becoming annoyed — possibly resulting in some choice words being thrown my way.

This is because the laws surrounding the documenting of strangers in public areas haven’t changed with the times. The amendment protecting the act of public photography was written in 1787 by men who lived in a world where cameras didn’t exist. Now the same law is being applied in an age where cameras are as countless as stars. A revamp on the laws surrounding photography etiquette in the U.S. is desperately needed.

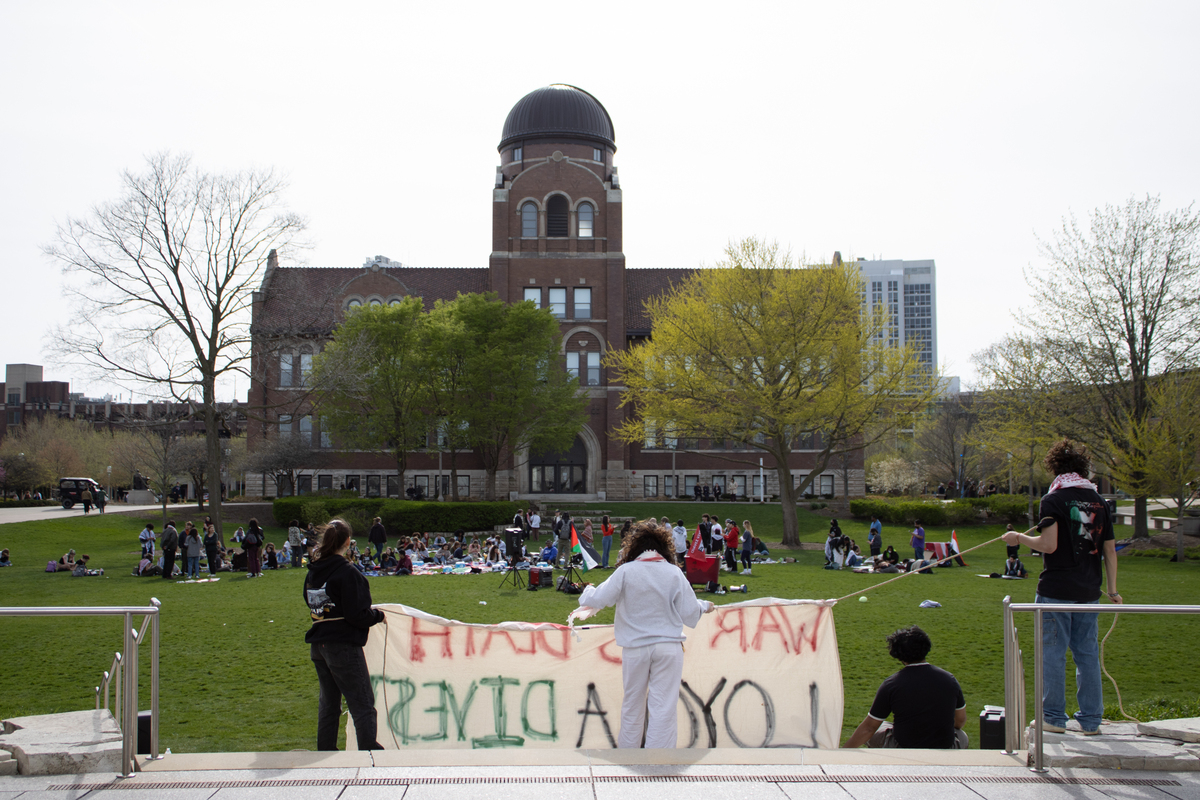

This isn’t to say public photography doesn’t have a place. There have been many cases where government oversight was carried out by people using their cell phone at the right moment. In times like these, a member of the public assumes the role of a citizen journalist, taking on the duty of reporting the news.

For example, citizen journalist Darnella Frazier was a bystander during the arrest of George Floyd. She took a video of police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on the neck of Floyd, which later became important evidence during trial, according to the Associated Press.

Frazier’s video is an instance where a member of the public is tasked with performing surveillance on the government. In cases such as these, the roles played by citizen journalists are indispensable and must be protected by law.

Citizen journalism, however, doesn’t include taking pictures of the average person going about their day. There have been countless viral TikToks where older adults are filmed eating alone in public. These videos garner responses of sympathy when they should provoke unease.

If someone was truly upset about seeing an older member of the public eating alone, the response should be to go eat with them. Secretly filming the individual from far away to harvest attention for themselves on social media is shady and corrupt.

These fake citizen journalists pretend their content is helping draw attention to a problem. In reality, it’s a self-serving practice that only creates uncomfortable situations for the victims being put into videos without their consent. The hypocrisy of the exploitative situation is palpable and far too common.

Hiding behind a screen to do one’s bidding is a prominent side effect of the tech generation. How many times a week are there photos or videos posted to Loyola’s college class Snapchat stories without a person’s knowledge or consent?

Most times, the perpetrator will try and play it off as if it is a giant game of neighborhood watch where members of the public have a duty to document anything they deem out of the ordinary.

Who is one person to decide what is ordinary or acceptable?

The simple act of drinking milk in the dining hall could get someone landed on the LUCMilked Instagram page, a profile which takes photo submissions of milk drinkers at Loyola. The account presents itself as a joke, but represents a bigger problem occurring among Gen Z. There is a clear disconnect between the power to take photos at any moment and the responsibility of knowing when it’s ethical to do so.

As a member of the public, you have a right to take a picture. But as a member of society, you have a duty to create an environment where everyone feels welcomed and free to express themselves. It’s not in good taste to overstep one’s boundaries to infringe on the privacy of members of the public.

Some things were only meant for your eyes, not to live in perpetuity on the internet — think before you click.

Feature image by Daphne Kraushaar / The Phoenix