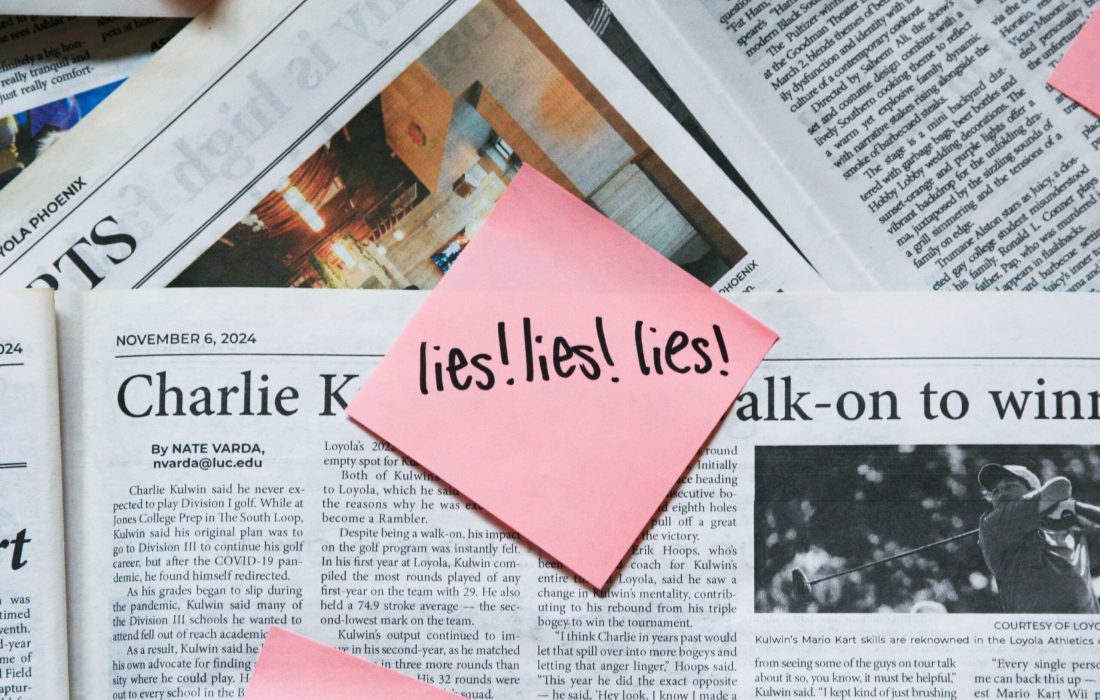

Staff Writer Seamus Chiles Troutman lies through his teeth about the benefits of not telling the truth.

Essay: Cross My Heart and Hope to Lie

In childhood, crowds chastised me with the familiar chant — “Liar liar, pants on fire.” But I never cowered. I had no shame, because I knew lying could make the world a better place.

Lying is often portrayed as a Machiavellian ploy for the deceitful and immoral. While many forms of falsehood are morally wrong, some lies inhabit a perfect middle ground — neither malicious nor inane.

White lies, or lies made to keep a secret an unpleasant truth, are commonly considered the one lie not inherently wrong to tell. If a longtime friend gets a buzz cut and tells themself they look like Brad Pitt — when in actuality they resemble Bobby Hill from “King Of The Hill.” — no good friend would call them the latter.

These lies support friends and protect people, but lying doesn’t require a profound moral purpose to be justifiable.

At times, the truth is overrated. The entire fiction genre is about creating interesting lies, whether they’re about space pirates or seemingly real people living seemingly real lives. Every old tale and fable was someone lying for another’s amusement, often addressed to children.

In truth, conjuring a creative lie is a dive into the recesses of the mind to access an imagination that once thrived in youth. Lying for the enjoyment of both parties exercises the human ability to find joy in the mundane.

Telling a lie doesn’t need to conceal the truth but can be used to simply enliven a conversation.

What’s a more interesting response when a grocery store cashier asks about your day — boldly replying, “I was chased by a shoal of piranhas while training to swim across Lake Michigan,” or “I pressed snooze on my alarm clock four times and ate a pack of microwave pizza bagels for breakfast.”

There’s nothing wrong with making a stranger’s day more interesting — even if it’s predicated on a lie.

Everyone loves a surprise in the monotonous story of a day. Look to movies as an example. A good movie surprises and adds intriguing developments to even a simple story. Would “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” be the same without its jumpscares or shocking deaths?

One day in seventh grade, I came home from school an hour late to see my parents waiting in the kitchen. They questioned my unusual tardiness, and instead of telling them the truth — that the school bus broke down — I told my parents I was at tryouts for the school swim team. This was a blatant lie, as my middle school didn’t have a swimming pool and I’d never swam in my life.

My family instantly knew I had lied, but my heart knew it was worth it for the story.

I’m a voracious liar. Whether it originated from nature or nurture I don’t know, but it’s become an unshakable habit. Even the story I just told is a complete fabrication.

As a child, my friends and I would sit at a lunch table and spin each other tales of the most outrageous events that never occurred, yet we told them with great conviction. Even though we all knew we were lying, we wanted to believe we lived those wild lives.

Am I wholly unique in lying? Many people lie without even paying attention to it.

People see others through a constructed filter on social media — not every side of a person can possibly be shown through 10 photos — so each human’s full truth is hidden. Someone can go on vacation and have a terrible time, but their Instagram followers will only see pictures of exotic food, nice weather and landscapes of astounding beauty.

It’s also fairly common for people to lie in job interviews about the extent of their experience to boost their chances of success. It’s even become a habit for men to adjust the truth of how tall they are.

Outlandish lies can act as a game, connecting others to a joyful tale separate from reality, yet built upon it. If you’re going to lie, go all out. Instead of a phony lie about traffic or a faulty alarm clock, tell everyone about your mountainous voyage or deep sea escapades.

Lying comes in all shapes and sizes, but the one lie most underutilized is a good story. When the fairytale from childhood doesn’t grow to be true, make it real for others — one lie at a time.

-

Seamus is a third-year student majoring in history and political science with a minor in European studies. As a staff writer, he likes writing comical stories and editorials on life as a college student. Originally from Chicago, Seamus enjoys listening to music, long walks on the beach and writing poetry in his sunroom.

View all posts

Topics

Get the Loyola Phoenix newsletter straight to your inbox!