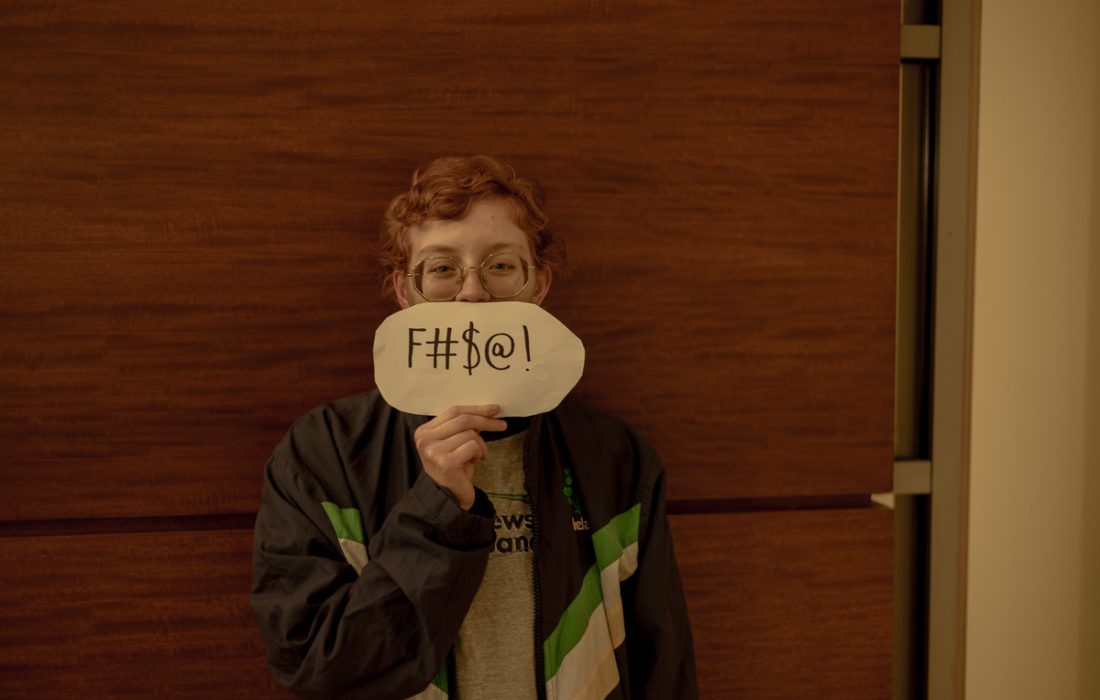

Writer Mao Reynolds talks about the positives of having profanity in media

Who Gives a #?!% About Profanity?

In 1972, comedian George Carlin was arrested in Milwaukee for profanity after performing his now-legendary routine “The Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television.”

Despite the massive social and cultural changes in the 52 years since Carlin’s arrest, those words are still taboo in news media, including broadcast news, newspapers and radio. Now, some people see swearing as unsophisticated, pointless and sometimes even illegal.

It’s bull$#!*.

My whole life, I was told people only swear because they weren’t educated enough, because they didn’t know better words to express their feelings. But studies show this isn’t the case. In fact, it’s the opposite.

When people swear, they release stress, according to a 2022 study on the physical effects of swearing in the academic journal Lingua. Swearing also jump-starts the part of the brain that produces adrenaline, a natural form of pain relief, according to The Science Times.

There’s not just a physical benefit to blaspheming, though — swearing is also a social skill. Using coarse language around others can signal a more relaxed, casual relationship between speakers, according to the Lingua study. It can also change a speaker’s tone, whether it makes threats seem more aggressive, emphasizes a certain point or adds an element of humor to an utterance.

So, when people swear, they aren’t uneducated — they’re actually flexing their linguistic muscles.

Languages change constantly, and the foul-word-filled field of English is no different. In the mid-1800s, the words “pants” and “trousers” were seen as scandalous because they had sexual connotations. And no, this wasn’t about underwear — this was literally about pants. Instead, newspapers called them “unmentionables,” “inexpressables” and “unwhisperables,” according to linguist Allen Walker Read. The word “ass,” which refers to both the human behind and the animal, used to be censored by publications but is becoming more and more acceptable in publications like The Wall Street Journal.

If we look at the greater scope of Western media, swearing has always been present, from crude comedies by Ancient Greece’s Aristophanes to titillating tales by Geoffrey Chaucer and provocative plays by William Shakespeare. From 2005 to 2010, instances of swearing on television rose by 69% — yes, that’s the exact percentage — according to The Hollywood Reporter.

Newspapers have changed with the times, too. The Associated Press, which most publications uses as a guide, lets uncensored obscenities slide if they appear in direct quotes or there’s a “compelling reason” for their use. More and more of news media have embraced unfiltered foulness, including late-night show hosts like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel and Conan O’Brien, according to the Brown Political Review.

Part of the skepticism around saucy language comes from legal barriers to publishing. The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution grants every American the right to free speech, including obscenities. However, there are certain exceptions, like the Communications Act of 1934 which banned the use of expletives on radio broadcasts. The 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation granted the Federal Communications Commission the power to decide which words can be said on-air or not.

However, obscenity can convey information more clearly to a newspaper’s audience.

When reporting on serious events like hate crimes and leaked recordings of politicians, printing profanity lets readers see the proof for themselves, like when The New York Times printed a comment by Monica Lewinsky including an uncensored F-word in 1998.

Without this explicit clarification, readers might not understand the weight of certain words — or obscene expressions in general, like the middle finger or hate symbols. Just a few weeks ago, Loyola released a statement about antisemitic graffiti found on campus, a statement which a student voice in The Phoenix criticized as vague. Being clear and explicit about the facts, no matter how rude they may seem, can help readers get the information they need.

As language changes, media should change, too — so we should embrace obscenity, whether it’s in a national newspaper or a local magazine.

-

Mao Reynolds is a fourth-year majoring in Multimedia Journalism and Italian Studies. He is Deputy Arts Editor and Crossword Editor for The Phoenix. When he’s not writing about the diversity of Loyola student life or reviewing neighborhood spots, he likes bragging about being from the Northeast and making collages from thrifted magazines.

View all posts

Topics

Get the Loyola Phoenix newsletter straight to your inbox!