A24’s “Spring Breakers” isn’t saying what it thinks it is.

‘Spring Breakers’ Is Still an Appropriative Mess, 10 Years Later

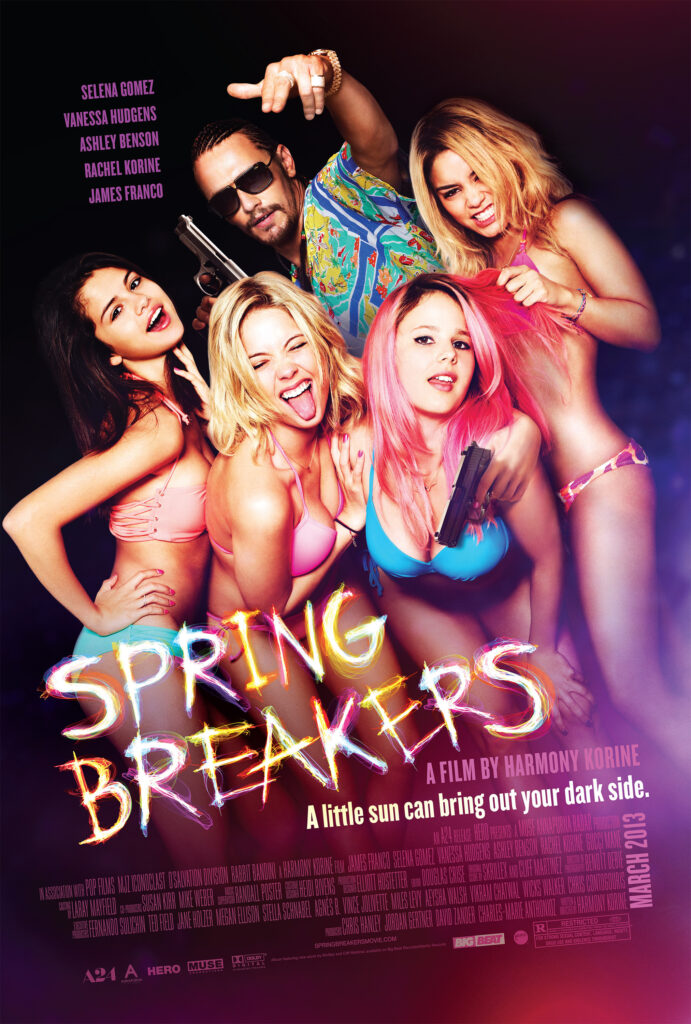

The lurid montages of bodies smashing together in the beating Florida sun in “Spring Breakers” turn 10 this month. Director Harmony Korine’s blown-out, neon shots of fraternity parties and cars on fire would go on to become an integral part of indie darling A24’s style.

Acclaimed indie studio A24, known for movies like “Everything Everywhere All at Once” (2022) and “Moonlight” (2016), has continued to define the world of the big-budget indie feature film since its inception in 2012. The studio also makes a lot of horror films, notably “Midsommar” (2019) and “Hereditary” (2018).

“The Bling Ring,” a movie also made by A24 around the same time as “Spring Breakers” captures what “Spring Breakers” lacks — a point. There’s a narrative reason for the hedonism its central characters engage in.

The central characters of “Spring Breakers” Brit and Cotty, played by Ashley Benson and Rachel Korine, as well as former Disney stars Selena Gomez and Vanessa Hudgens, who play Faith and Candy, wander from scene to scene with no real direction or symbolic meaning.

The film served as a vehicle for Hudgens and Gomez to break out of the puritanical Disney bubble and prove to audiences they were no longer the starlets they once were for Mickey. Both actresses expressed in an interview with The New York Times upon the release of the movie that they no longer wanted to be seen as Disney actresses, but as just actresses.

Hudgens and Gomez would go on to pursue more serious roles and careers in films released that same year. Hudgens made an appearance alongside Nicholas Cage in the film “Frozen Ground” and Gomez continued to devote herself to her burgeoning music career following the release of her album “Stars Dance” in January 2013.

The film itself doesn’t follow any cohesive plot. It chronicles the descent of the spring breakers into further spheres of debauchery and crime, cut into thirds by the departures of Faith and Cotty. The film ends with Brit and Candy driving away in a stolen car, leaving the audience wondering what the point of the film could’ve possible been.

James Franco plays Alien, a rapper the girls saw performing on the boardwalk earlier in the movie who later bails them out of jail after they’re arrested for drug possession. His motivation isn’t clear to most of the girls, but it’s clear to the audience he intends to exploit them in some way.

Uncomfortable with Alien and his career as a drug dealer, Faith leaves Florida and goes back to school, followed by Cotty a few scenes later. The film culminates in a shoot-out with Alien’s nemesis Archie, played by Gucci Mane, in which Alien dies and the two remaining girls, Brit and Candy kill Archie.

The film is often lauded as a critique of the hedonism of American youth and the ways in which society will collapse in the face of carefree and troublesome college girls, according to a review in The New Yorker. Instead, Harmony Korine delivers something far shoddier than a satire on the neon downfall of American culture critics often think he has.

“Spring Breakers” intends to be provocative in an intelligent way, instead it’s provocative just to be provocative and lacks the satirical nature that Korine seems to think it has. It consistently falls flat in between nonsensical sequences of the spring breakers who, with the exception of Gomez’s character Faith, are completely interchangeable and unremarkable.

Faith’s character is established early on as a “good girl,” and doesn’t accompany the rest of the girls in their plot to rob a chicken shop in order to get the money they need to go on spring break. She is naive, religious and meant to show how outlandish the antics of the rest of her friends are. It’s for these reasons she’s the first to leave the trip.

The direction follows the visual cues of the music video for Fiona Apple’s hit song “Criminal” — every shot feels objectifying and grungy in a demeaning and uneasy way. However, Apple’s womanhood and lyrics are explanations for her cinematic choices, unlike Korine whose masculinity shades his shots from clear contextual reason. Male director Korine seems to use these kinds of shots without any clear contextual reason.

The film makes heavy use of the female body in an exploitative and gratuitous way. The men throughout the film are often scantily clad but it is more often the women who are topless or naked. “Spring Breakers” tries to critique the appropriation of Black culture by white artists in the same way it attempts to critique the hedonism of American youth, which is by just showing it on screen.

While the movie intends to comment on the problematic nature of white appropriation of Black culture, specifically in regard to rap music, it instead comes across as an endorsement of that practice, according to a master’s thesis written by John Francis Donegan.

“They are privileged Hollywood artists exploiting African American aesthetics in the name of irony and comedy,” Donegan wrote.

The film combines shock value and attempted cultural critique in the hopes that audiences won’t be able to tell the difference. “Spring Breakers” is a film so shallow that it feels as though Korine hopes pretentious art students will think so hard about the film they make up a meaning for him.

“Spring Breakers” pretends to be smart and it wants the audience to think that Korine is just as smart as the film is. But Korine lacks the directorial hand to implement any kind of satire or critique leaving the movie a gross hour and a half of exploitation and appropriation with no clear reason or end.

Featured image courtesy of A24