Loyola professor Marina Ross created a beautiful collection of paintings exploring grief and nostalgia for gallery show, Everything was Forever.

In a small, white gallery with large windows overlooking Pilsen’s urban landscape, several colorful paintings cover the wall. Enticing colors and bold brushwork draw viewers in, creating an indelible experience.

Marina Ross, an art professor at Loyola who was born in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, is the artist behind Everything was Forever, a gallery shown at Baby Blue Gallery (2233 Throop St.) from Dec. 3 to Jan. 14.

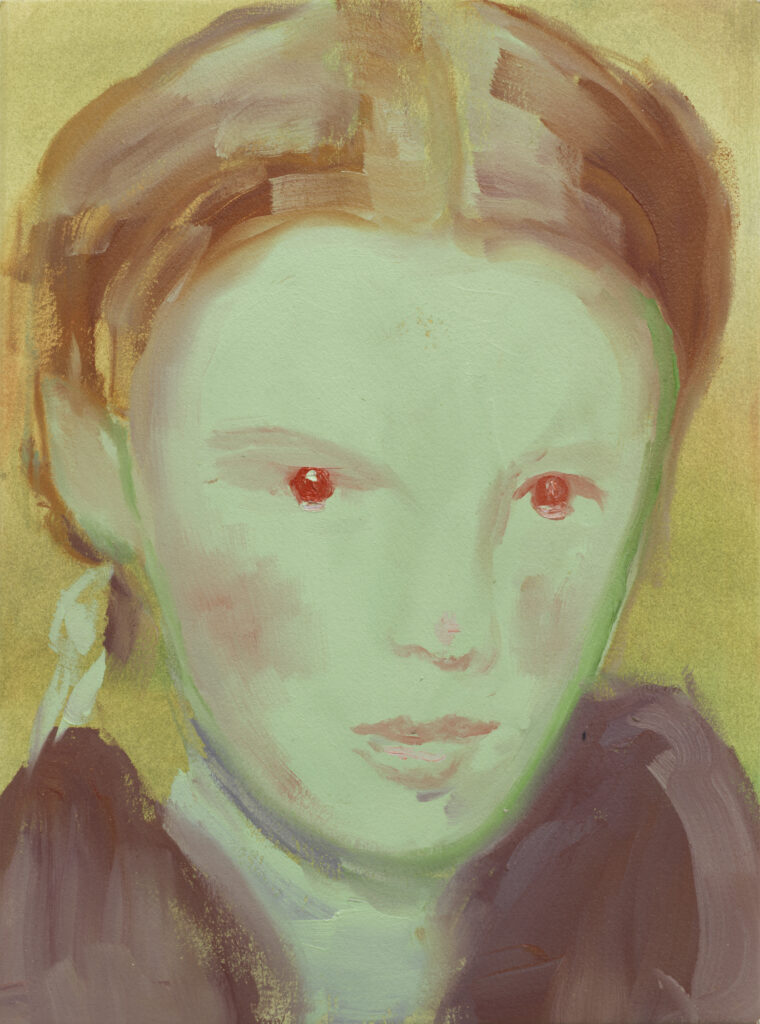

The show featured 12 artworks depicting still images taken from the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz.” The paintings have an ethereal quality, featuring pastels that make the compositions feel like a portal into another realm.

“Everybody has seen it and everyone has a memory of it and I think I wanted to access that,” Ross, 32, said. “I remember my mom got it for me as a kid and that’s just like the one movie I remember she got for me. So it’s personal in a way, but it is also sort of universal.”

Caleb Beck is a co-director of Baby Blue Gallery where Ross exhibited her work. When he first encountered Ross’ artwork, Beck said he appreciated her use of color and the sincerity of her work.

“It’s a sincere personal connection, it’s not pop art commentary on the ‘Wizard of Oz’, right, like this kind of blown-up version of Dorothy where you’re supposed to view her as a cultural text rather than a person,” Beck, 30, said. “She’s both a person and a cultural text and actress. She’s all of them.”

Ross uses close-ups of Dorothy’s face multiple times in the show — the variations of Garland’s portrait reveal several sides of the young star. In some versions, she appears like the 16-year-old girl she is, young and naive of the danger awaiting her in Oz and Hollywood.

In other works, Garland has a confrontational glare ranging from sweet to hostile — her gaze is powerful. In the painting “Constellation,” Dorothy has pale green skin and bright red eyes, giving her a reptilian stare that pierces into the viewer from across the room.

Judy Garland as a subject falls in line with Ross’ long-standing interest in iconic female performers and the often tragic narratives that surround them. Ross cites examples including Marilyn Monroe, Britney Spears and Brittany Murphy. Ross said she is interested in taking back the rise and fall narrative around American female performers.

There are many dark facts about the filming of “The Wizard of Oz” that have seeped into the collective unconscious and imbue the art with a darker connotation. Facts like Buddy Ebsen being poisoned by the aluminum makeup used to turn him into the tin man and Judy Garland’s claims she was given uppers and sleeping pills to keep up with the demands of filming, as reported by TIME.

These facts generate unnerving questions about what it takes to construct a beautiful fantasy and what may lurk beneath the surface concealed by whimsy.

“I think as you grow older, you start to learn more about what happened on set and the way that Judy Garland was treated and how she suffered,” Beck said. “So the subject matter of ‘The Wizard of Oz’ and its context are very alluring and captivating to people.”

The artworks featured have a very personal nature beyond the nostalgic connection. The paintings also delve into Ross’ personal relationships and tragedy.

“There’s No Going Back” depicts Dorothy, painted iridescently next to Glinda the Good Witch who fades into the background like a specter, comforting yet slightly menacing. Ross said the relationship between Glinda and Dorothy in this piece is partly representative of the complex relationship between daughter and mother.

“Dorothy was looking down like she was kind of having this moment with herself of trying to figure out like, ‘What do I do?’ And I kind of think of the good witch as my mom, like you know you’d never do what your mom says, but you know she’s right,” Ross said.

Just a month and a half before finding out she was offered the gallery show, Ross experienced the loss of her two-year-old son, Rafi, who died in June. She said she was determined to not let the devastating experience destroy her, and the work is in many ways a manifestation of her unique experience of grief.

“My work has always been about loss and death. Like I’ve always looked at dead female performers like Brittany Murphy,” Ross said. “Her death really traumatized me, because she was just this like emblem of success and beauty and she’s just so beloved, and same with Judy Garland. I don’t know, maybe Rafi kind of represents that, too. He’s this beloved person and also represents tragedy.”

Ross’ personal experience with grief has manifested into a collection of images that openly depict vulnerability. In addition to being visually compelling, Ross’ insights infuse the artworks with incredible depth and emotion.

Ross’ use of pastel hues of green and pink combined with fantastical and childlike imagery recasts notions of how grief is depicted in art. Ross said the brightness was an intentional choice she made when creating the work.

“I think at the time, I was feeling like I wanted the sense of fantasy. I was like, ‘This horrible thing happened,’ and the movie represents fantasy and comfort and sentimentality and nostalgia,” Ross said.

Ross said she sees the performance of femininity and celebrity as analogous to her own performative recovery, in which she attempts to ease the discomfort other people experience through her grief. The show revolves around the questions of how to go back into the world and continue to function after intense tragedy.

“For me, the answer was a performance that you have to perform a new identity that you create for yourself,” Ross told The Phoenix

“Invisible Layer” is a 35 x 45 inch painting that utilizes a monochromatic green color scape and depicts Dorothy in the Emerald City as she is about to receive a makeover. Dorothy is seated in the center while three tall and smiling figures huddle around her.

Ross said this work in particular speaks to themes of performance and the female body as a site of transformation.

“They’re kind of like portraits of me, grappling with my own identity as a woman, a mother, an artist,” Ross said. “Then this one has that sense of community and how people impact you. Over the last six months, I’ve developed so many relationships with people who changed my views of myself as an artist, so I guess it kind of speaks to them.”